Eureka Day

By Jonathan Spector | Directed by Lili-Anne Brown

Dr. DeRon S. Williams Production Dramaturg

Grace Herman Assitant Dramaturg

WELCOME

Welcome to your Eureka Day Dramaturgy Resource!

You can use the menu to the left to navigate the content or just scroll through!

This is a live document where we I will continue to add resources as we work through this production. With that, please reach out if you need help finding information, are particularly curious about something, or if there is anything we can do to help support you dramaturgically. We will both be in and out of rehearsals so please feel free to ask questions at any time, but if you don’t catch us you can always shoot us an email.

Contact Information:

Dr. DeRon S Williams: deronwms@gmail.com

Grace Herman: gsherman723@gmail.com

Table of Contents

About the Playwright: Jonathan Spector

“Jonathan Spector is Tony Award-winning playwright based in Northern California, whose work has been produced on and off Broadway, regionally, and internationally. His plays include EUREKA DAY (2025 Tony Award, Drama Desk Award, Drama League Award, for Best Revival); THIS MUCH I KNOW (New York Times Critics' Pick, Edgerton Award); BIRTHRIGHT (upcoming at MCC Theater); BEST AVAILABLE (Elizabeth George Commission); and SIESTA KEY.

Spector’s plays have been produced at theaters across the country including Manhattan Theater Club, Aurora Theater, Theater J, Pasadena Playhouse, Marin Theater, 59E59, Miami New Drama, Asolo Rep, Syracuse Stage, InterAct, Shotgun Players, Mosaic Theater, Colt Coeur, and Just Theater. His work has also been seen at some of the world's leading theaters including London's Old Vic, Vienna's Burgtheater, and Dublin's Gate Theater (upcoming).

Honors include two Glickman Awards for Best Play to premiere in the San Francisco Bay Area, two Bay Area Theater Critics Circle Awards, Rella Lossy Award, Theater Bay Area Award, and a WhatsOnStage Award Nomination. He has been a Playwrights Center Core Writer, TheatreWorks Core Writer, MacDowell Fellow, SPACE at Ryder Farm Resident, Playwrights Foundation Resident Playwright and is currently working on commissions from Roundabout Theater Company, La Jolla Playhouse and Manhattan Theater Club, His work is published by Dramatists Play Service/Broadway Licensing.

Jonathan is a graduate of the much-besieged New College of Florida and holds an MFA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State. In his misspent youth as an aspiring director, he was a member of the Soho Rep Writer/Director Lab, the Lincoln Center Directors Lab, a frequent collaborator with The Civilians, and a dealer at New York's largest underground poker club. He is represented by CAA and Kaplan/Perrone Entertainment.”

Playwright Interviews

Jonathan Spector: What the Play Wants

An interview with the playwright of ‘Eureka Day’ about creating the play in a pre-Covid world and seeing the show anew through a changed society.

Jonathan Spector’s play Eureka Day follows several contentious parents’ meetings about vaccine policies at a Berkeley private school. Originally staged in 2018, the play is currently running on Broadway at the Manhattan Theatre Club. He spoke before rehearsals began—and before the 2024 presidential election—with the play’s director, Anna D. Shapiro, as she recovered from Covid.

ANNA D. SHAPIRO: It’s hysterical to me that I’m talking to you from my Covid sick bed. It made me think about this play, and how long you’ve been living with it and where it started, in terms of what questions you were asking with it, and where you find yourself as it’s about to go to Broadway. Have the questions shifted? Has your focus shifted?

JONATHAN SPECTOR: In a weird way, it’s both the same and different. When I began working on it, I was really just trying to write a very Berkeley play about a very specific place and a very specific group of people. The reason vaccine skepticism seemed like an interesting thing to explore was because, at that time, it was the one issue where you could have people who basically all agree about everything except for this one thing. In doing research, I had spent a lot of time in the dark recesses of weird message boards and grappling the strange beliefs people had. This was also in the lead up to the 2016 election, so it was also a scary moment of realizing how the whole country was living in these two very separate realities. So that was informing it. But it still felt very particular to the place, and also to an issue that, unless you happen to have school-age kids or a new baby, you probably didn’t spend a lot of time thinking about. It felt very private—like, this is a play for Berkeley, about Berkeley, made by people in Berkeley, on an issue I had become obsessive about but most people don’t really care about that much.

To have it sort of explode out to be, like, an issue the entire world is obsessed with was very strange. Although there’s also a way in which this may be a perfectly goldilocks moment to be doing it. In the pre-Covid period, it had three or four productions, and people at that time were more able to see the vaccine debate as sort of a metaphor for democracy and society. Two years later, when theatre was just coming back, it seemed like all anybody could see was it being somehow a play about Covid. But now we’re in this very weird place where we’re “over” Covid—but obviously not, since you have it—and we’re trying to navigate this strange space of making choices, individually and collectively, about balancing the needs of society to get back to life and the need to allow people who are immunocompromised to exist in society. We’re in this place of nobody really being sure anymore what the answers are to those questions, and everybody kind of navigating it differently, and people still feeling very intensely on one end of the spectrum or the other about what everyone should be doing. I think that makes it an interesting time to do the play.

At the same time, the experience of watching the play with an audience is very similar to the experience of watching it with an audience pre-Covid. The audience is responding to the same moments in the play in largely the same way. Which makes sense, because people react to specific things humans do onstage and not to their shifting feelings about abstract ideas on viruses and public health.

Photo: Jeremy Daniel

Production History

The road to Timeline Theatre

Eureka Day premiered at Aurora Theatre Company in Berkeley, California in 2018. From there it moved to New York in 2019 for an Off-Broadway production. When the theatre world picked back up about the COVID 2020 shutdown Eureka Day jumped across the pond for a sint at London’s Old Vic in 2022. Then, it returned to New York city in November of 2024 for its Broadway Premiere at the Manhattan Theatre Club. In 2025 Eureka Day spread across the maps with 8 different productions from the Pasadena Playhouse in California to Nottingham Rep in the United Kingdom. It was also slated for a run at the Kennedy Center in 2025, but was cancelled. Eureka Day has won plenty of awards including the 2025 Tony for Best Revival of a Play, as well as the Drama Desk Award and the Drama League Award for the same category.

Reviews

"So brilliantly yoked to the current American moment—its flighty politics, its deadly folly—that it makes you want to jump out of your skin...I’m still trying to figure out how hard is appropriate for a critic to laugh at the theatre; this night, I made myself hoarse."

- Vinson Cunningham, The New Yorker

"Reaches a peak of hilarity that would make Oscar Wilde envious. It’s that good. There wasn’t a soul in the theatre not convulsed with laughter...it is a shockingly beautiful piece of writing."

““Eureka Day” doesn’t have an answer for how to fix this sorry state of affairs, but that it poses the question makes it a play with an unusual amount on its mind, and a fine night of theater that will fuel post-show conversation long after the curtain falls.”

“The show is a polite tiptoe along a cliff, a trek across a field of eggshells that as often as not are strewn atop landmines. Spector has a keen ear for the particular dialect adopted by liberal communities in the aftermath of the first Trump election. For many at this point, it’s a cringily familiar patter: soft-spoken, high-strung, defensive, apologetic, riddled with anxiety. A messy blend of earnestly caring and desperately attempting to perform that care. The terrified dance of the well-intentioned.”

- Sara Holdren, New York Vulture

“Every character gets to land a fair punch, or make a good point, as well as appear both risible and ridiculous. At Eureka Day, as in most places, most people are well-meaning, often deeply misguided, trying to make sense of what limited knowledge and life experience they have.”

Mumps

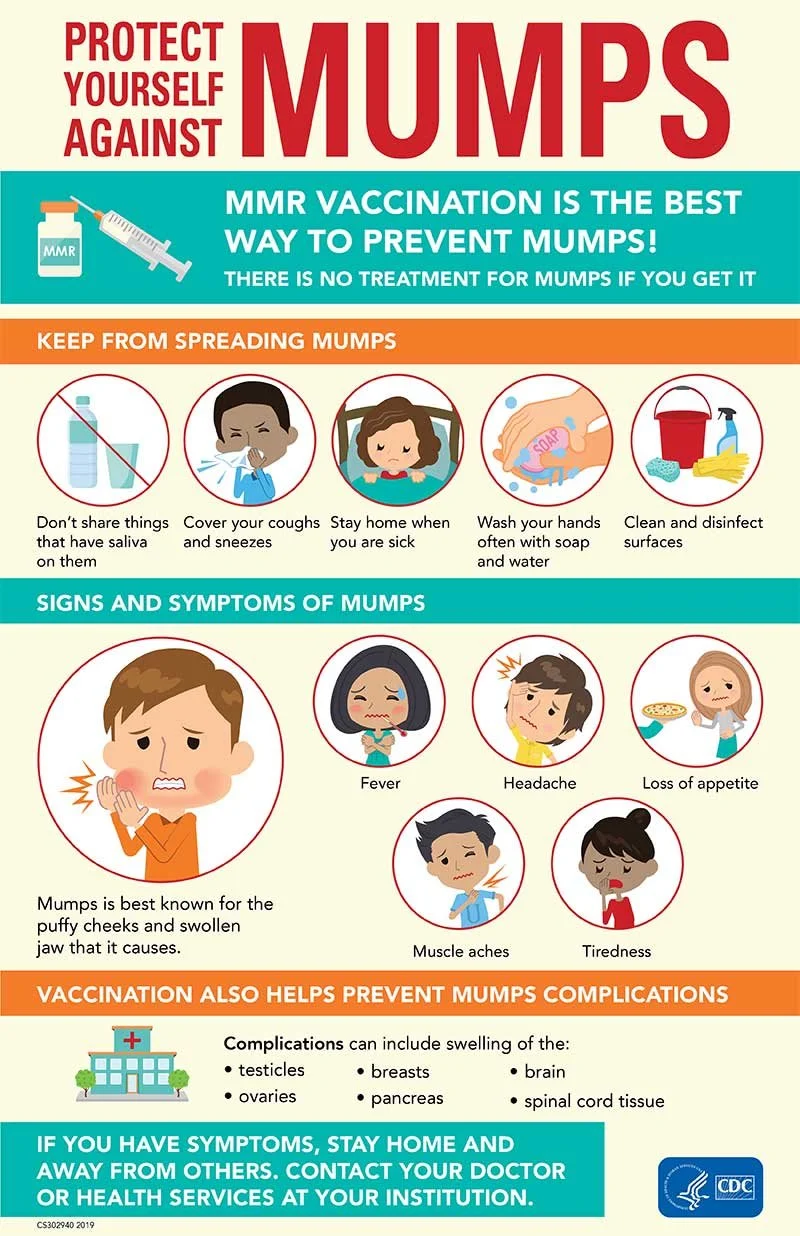

Mumps is a contagious and infectious viral disease that causes swelling of the parotid salivary glands in the face. It is an airborne disease spreading easily through coughs, sneezes, or by sharing items like contagos. It’s contagious from a free day before symptoms start until 5-9 days after swelling begins.

-

Swollen and tender salivary glands, causing puffy cheeks/jaws.

Fever, headache, muscle aches

Tiredness, loss of appetite

Difficulty chewing, swallowing, or talking

Earache

-

On rare occasions mumps can lead to serious complications like Meningitis (inflammation of brain/spinal cord lining), pancreatitis (inflammation of pancreas), Orchitis (testicle inflammation), Oophoritis (ovary inflammation), deafness, miscarriage.

-

Mumps treatment focused on support care like rest, fluids, and pain relief. Doctors emphasize that prevention is key with the MMR vaccine providing long lasting immunity. If infected individuals should stay home for 5 days to prevent the spread.

Recent U.S. Statistics

2024: 357 reported cases.

2023: 429 reported cases.

2021-2023: Lower incidence than pre-pandemic, but mumps remains endemic; younger children (1-4 years) saw the highest rates.

2018-2019 Outbreaks: Significant outbreaks occurred, particularly among adult migrants and in university settings, with nearly 900 cases in detention facilities alone.

Pre-Vaccine Era

Before the U.S. mumps vaccination program started in 1967, around 150,000 to 186,000 cases occurred annually.

Vaccine Impact & Outbreaks

The MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) vaccine is highly effective, but outbreaks persist, often in communities with lower vaccination rates, affecting unvaccinated young adults (18-24) and sometimes children.

Key Takeaways

Mumps is far less common now, but still present in the U.S..

Outbreaks are often linked to unvaccinated individuals, particularly young adults in close-contact environments like colleges.

Maintaining high MMR vaccination coverage is crucial to prevent resurgence.

Mumps Vaccine

The mumps vaccine is a live, weakened virus given as part of the MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) vaccine. It is given in two doses, around 12-15 months and 4-6 years. Research around the vaccine began in the 1940s, but the first licensed vaccine Mumpsvax came out in 1967. It was created by Maurice Hilleman using the “Jeryl Lynn” strain from his daughter. Then 4 years later it was quickly followed by the combined MMR vaccine in 1971.

The Mumps vaccine was the fastest vaccine ever developed, before the COVID-19 vaccine. The story goes, Maurice Hilleman american microbiologist who specialized in vaccinology (developing over 40 vaccines in his life time) and ran the pharma company Merck’s vaccine and virus research division was woken up one night in 1963 by his five year old daughter Jeryln Lynn, sick with the mump. He collected swabs of the virus strain from her and used it to develop the Mumpsvax in a record breaking 3 years.

Mumps Vaccine Timeline

History of Vaccines

“For centuries, humans have looked for ways to protect each other against deadly diseases. From experiments and taking chances to a global vaccine roll-out in the midst of an unprecedented pandemic, immunization has a long history.

Vaccine research can raise challenging ethical questions, and some of the experiments carried out for the development of vaccines in the past would not be ethically acceptable today. Vaccines have saved more human lives than any other medical invention in history.”

-

1400s-1700s: People in different parts of the world attempted to prevent illness through variolation. By intentionally exposing healthy people to smallpox. Some sources suggest this was taking place as early as 200 BCE.

1721: The practice of smallpox inoculation was brought to Europe. When Lady Mary Wortley Montagu asked that her two daughters be inoculated after she observed the practice in Turkey.

1774: Benjamin Jesty discovers that infection with cowpox could protect humans from smallpox.

1796: Dr. Edward Jenner created the world’s first successful vaccine, using Jesty’s discovery he infected people with cowpox making them immune to smallpox.

1872: Louis Pasteur creates the first laboratory-produced vaccine.

1885: Louis Pasteur successfully prevents rabies through post-exposure vaccination.

1918-19: The Spanish Flu pandemic kills 20-50 million people worldwide making an influenza vaccine a US military priority.

1937: The yellow fever vaccine is developed by Max Theiler, Hugh Smith and Eugen Haagen.

1945: The first influenza vaccine is approved for military use in the US.

1946: The first influenza vaccine is approved for civilian use.

1952-1955: The first effective polio vaccine is developed by Jonas Salk. Mass trials being involving over 1.3 million children.

1960: Albert Sabin develops a second type of polio vaccine and it is approved for use.

1963: The measles vaccine is license and introduced for public use.

1967: Mass vaccination begins with the World Health Organization announcing the Intensified Smallpox Eradication Program. Where they aimed to eradicate smallpox in more than 30 countries through surveillance and vaccination.

1967: Mumps vaccine is created.

1969: Rubella vaccine is created.

1971: The measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine are developed into a single vaccination by Dr. Maurice Hilleman.

1974: The Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) is established by WHO, the first diseases targeted are diphtheria, measles, polio, tetanus, tuberculosis, and whooping cough.

1978: A polysaccharide vaccine that protects against 14 strains of pneumococcal pneumonia is licensed.

1980: Smallpox is declared eradicated.

1988: WHO launches the Global Polio Eradication Initiative

2006: HPV vaccine is approved.

2019: WHO prequalifies an Ebola vaccine for use in countries at high risk.

2020: WHO Director General declares the outbreak of COVID-19 to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and later confirms it is a pandemic.

2020: In December the first COVID-19 the first vaccine doses are administered.

2021: COVID-19 Vaccination is rolled out around the world.

VACCINE HESITANCY

Meeting The Challenge of Vaccine Hesitancy

Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine September 2024, 91 (9 suppl 1) S50-S56; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.91.s1.08

Oluwatosin Goje, MD, MSCR, FACOG and Aanchal Kapoor, MD, MEd

ABSTRACT: Vaccination is a cornerstone of public health, but vaccine hesitancy poses significant challenges as highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addressing the challenge requires healthcare professionals to effectively counter misinformation. They have a pivotal role in fostering trust and promoting evidence-based vaccine recommendations, with tailored communication strategies and community engagement initiatives. Legislation, policy interventions, research, innovation, and technology are needed to enhance vaccine uptake and ensure equitable access. Integration of vaccination into routine healthcare is paramount for public health protection against emerging infectious threats.

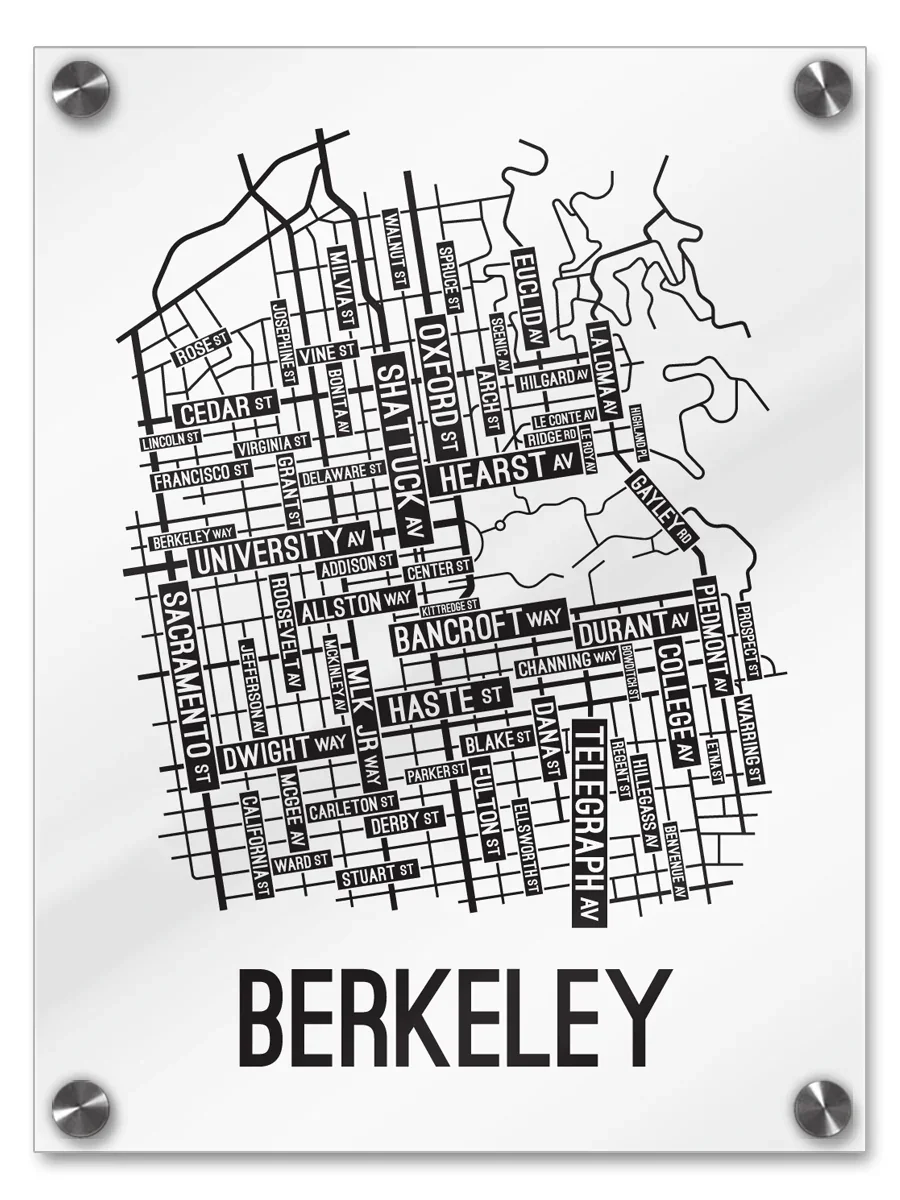

Berkeley, California

Highly educated populations with bachelor’s degrees or higher tend to vote for more liberal candidates. In Berkeley, 75.02% of all adults have earned a bachelor’s degree or higher. Educated women are far less likely to vote for conservatives, and in Berkeley, women make up 51.46% of the population.

Older Americans tend to vote more conservatively. Members of the Boomer and Silent generations (born 1928-1964) more often vote for Republicans, while GenX, Millennials (born 1965-1996), and younger generations consistently support Democrats. The median age in Berkeley is 37.1, which is younger than the national median age of 38.1.

Is Berkeley a political battleground? Across all types of political contests in Berkeley, including state, local, and presidential elections, races come within five percentage points 0% of the time.

-

Population: ~120,000 (2023).

Racial/Ethnic Diversity: Roughly 53% White, 20% Asian, 12% Hispanic, 7.5% African-American (city-wide).

Housing: Mostly renters, competitive and expensive market.

Vibe: Urban-suburban mix, cultural hub with many amenities.

-

Median Household Income: $108,558.

Per Capita Income: $66,936.

Poverty Rate: 16.8%.

-

Acceptance Rate: 11%.

Student Demographics (US): High Asian (39.8%), Hispanic (24.6%), White (22.1%) representation.

Top Majors: Natural Resources, Architecture, Legal Studies, Math & Statistics.

Department Strength: A global leader in Statistics, AI, Machine Learning, and data science.

-

Overall Crime Rate: Higher than the national average, with property crimes being common.

-

Home to UC Berkeley & Lawrence Berkeley National Lab.

Known for cultural events, diversity, and unique local businesses.

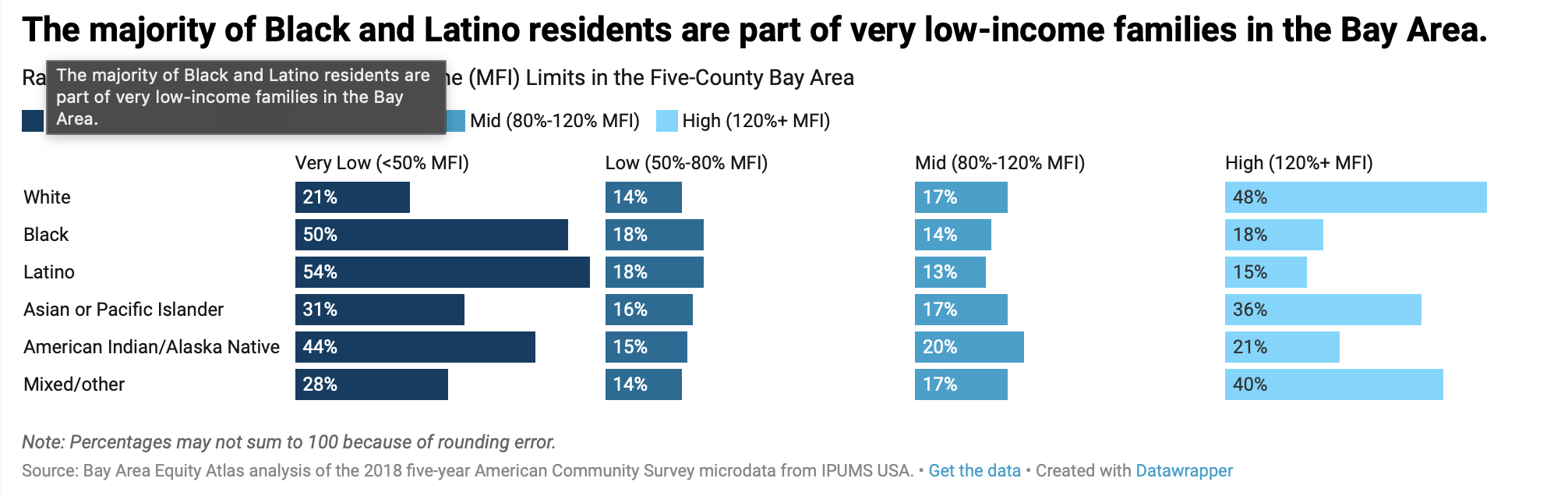

Skepticism, Survival, and the State: Race and the Politics of Public Health Trust

Skepticism toward public health institutions in Black communities is often misunderstood as hesitation, misinformation, or resistance to science. However, when examined through a historical and structural perspective, skepticism is not a flaw but a logical response. It is rooted in generational memory and built on centuries of medical exploitation. Black mistrust acts as a survival strategy—an understanding shaped by lived experience rather than abstract theory. Jonathan Spector’s Eureka Day, although set within a predominantly white progressive context, serves as a crucial space for exploring these issues. The play shows how public health discourse often assumes a universal trust without acknowledging how race fundamentally influences access, vulnerability, and belief.

The roots of mistrust stem from the early history of American medicine. During slavery, medical knowledge was often gained through experiments on enslaved people without their consent, anesthesia, or proper care. Black individuals were treated as research subjects rather than patients. This exploitation continued after emancipation, with forced sterilizations, segregated hospitals, and unethical clinical studies into the 20th century, all of which reinforced racial hierarchies within public health. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study is perhaps the most well-known example—not because it is unique, but because it exemplifies ongoing harm. It serves as a reminder of the government's willingness to sacrifice Black lives in the name of science and national interest.

This context clarifies that mistrust is not an irrational emotional reaction. It is a historically justified judgment of institutional behavior. When public health systems have repeatedly failed or endangered Black communities, skepticism serves as a form of protection. In contrast, Eureka Day depicts a community where institutional trust is often assumed. The play examines how progressive ideals of consensus, inclusivity, and dialogue break down under the pressure of a public health crisis. However, the play’s framework presumes that institutions ultimately serve the community’s best interests—an assumption that cannot be universally applied when these systems have long failed to protect Black lives.

In contemporary America, the legacy of medical racism remains evident. Black maternal mortality rates are disproportionately high, medical pain is often under-assessed for Black patients, and public health crises disproportionately impact Black neighborhoods. Technological systems designed to improve care can still perpetuate inequity through algorithmic bias. These patterns show that mistrust is not just inherited memory; it is continually renewed by ongoing violations. The system that caused historical harm still influences outcomes today.

By positioning Eureka Day alongside this history, the absence of race in the play becomes meaningful. It reflects the wider cultural tendency to universalize public health discussions—treating "the public" as if all experience the system similarly. Yet, true consensus exists only when participants believe that the system works for them. Black communities do not have equal access to that belief. The play then serves as a lens to explore the limits of collective trust. It shows how ideas of community break down when trust is assumed rather than built.

If public health aims for greater equity, trust shouldn't be seen as just a behavioral problem to fix. Instead, it should be viewed as a relational matter that needs repair. Institutions must recognize past and current harm, work on rebuilding trust through accountability, and prioritize Black voices in decision-making. Skepticism shouldn't be met with punishment but with understanding that it often comes from lived experience, not ignorance.

Public health trust, then, must be built through structural change—not just rhetorical persuasion. Repair requires more than outreach efforts or culturally aware messaging. It calls for policy changes, resource reallocation, and a commitment to transparency. It demands that institutions clearly show, in tangible ways, that Black lives are valued and protected.

Seen through this perspective, Eureka Day resonates not because it depicts the Black experience but because its thematic concerns reveal how fragile trust becomes when it lacks historical context. The play exposes the tension between ideology and lived reality, between belief and risk. In relation to the history of Black medical skepticism, it emphasizes that trust is not a neutral expectation but a political and historical negotiation.

Skepticism in Black communities is not a rejection of public health; it is a memory of survival. It stems from a long history of state violence and medical neglect. Until institutions directly address this history, mistrust will remain justified—not as resistance to progress, but as a protective strategy in a system where harm has been the norm rather than the exception.

SCHOOL TYPES

The Ultimate Guide to 13 Different Types of Schools Across America

By Brianna Flavin on 07/04/2016

Looking into school options can feel like trying to sort threads in a tapestry. Everything is woven together and jumbled around in ways that takes a lot of research to parse. Terms like montessori, magnet or parochial might send you on a tangent search just to get some definitions. There are difficult decisions to make when finding the right school without the added confusion of different types of schools. That is why we compiled some of the research for you.

Almost every type of school can be sorted into the public or private category based on its funding. Public schools receive their funding from the government and private schools receive funding anywhere else. While most schools can fall into these two categories, the standard public vs. private school breakdown scarcely touches the wide array of schools you can find.

With that in mind, we’ve sorted 13 different types of schools by their primary source of funding. Read on for a guide to school choices in the U.S. and narrow your search for the perfect school.

Read through them all to compare or click on the link below to head straight to the type of school you’re seeking.

-

Holistic retreat and nonprofit educational institute, considered the epicenter of the human potential movement. The Human Potential Movement is a 1960-1970s cultural and psychological framework rooted in humanistic psychology focused on unlocking untapped human potential for self-improvement, growth, and fulfillment.

-

Corps of American diplomats and professionals who represent the U.S. Abroad.

-

Using or expressing dry, especially mocking, humor.

-

Russian-born American writer and philosopher who developed the philosophical system of Objectivism. Objectivism is a philosophy that asserts reality exists independently of our thoughts or feelings, and that reason is the only way to know it. It holds that individuals have free will and the moral purpose of life is to achieve one's own happiness through rational self-interest. Its main pillars are: objective reality, absolute reason, individualism, and laissez-faire capitalism.

-

A fundamental, actionable guideline that dictates how a team or organization behaves, makes decisions, and achieves its goals

-

Being present, non-judgmental, and supportive while another person experiences something difficult, such as grief, a difficult conversation, or a personal journey

-

Elementary school in Berkeley California.

-

The fundamental physics framework explaining matter and energy at atomic/subatomic levels

-

Highest mountain in Africa

-

An ethnic group from Nepal renowned for mountaineering, their Tibetan-Buddhist culture, and high-altitude endurance; it also broadly describes local guides/porters in the Himalayas.

-

A week-long event in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert focused on "community, art, self-expression, and self-reliance".

-

Is a book published in 1970, it’s a comprehensive women’s health guide covering sexuality, reproductive health, healthcare reform, body image, and activism.

-

Autobiographical novel by Henry Miller that is notorious for its candid sexuality.

-

A community school is any school serving pre-Kindergarten through high school students using a “whole-child” approach, with “an integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development, and community engagement.

-

A cry of joy or satisfaction when one finds or discovers something. Also a really city in California.

-

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons.

-

Census-designated place in Los Alamos Country, New Mexico famous for its role in the Manhattan Project, where scientists at the secret Los Alamos National Laboratory developed the world’s atomic weapons.

-

Being impartial, objective, and free from personal biases, beliefs, or judgments when observing, researching, or reporting on something, aiming to present facts without emotional influence or moral evaluation.

-

A participatory method where diverse community members engage in structured, meaningful dialogues to build understanding, address local challenges (like health, education, or inclusion), identify shared goals, and collaboratively develop actionable solutions.

Work Bank

-

General agreement or a collective opinion reached by a group.

-

To have an ownership share or significant interest in something.

-

The MMR vaccine protects against measles, mumps, and rubella, typically given in two doses: the first at 12–15 months and the second at 4–6 years old.

-

The first person identified in an outbreak of a contagious disease.

-

Ornate coffin from ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman cultures. Considered an eternal home reflecting the deceased status and beliefs through carvings and texts.

-

A fiduciary is a person or entity legally bound to act in the best financial interests of another

-

A mandatory, temporary break from work, often unpaid, where employees remain technically employed but stop working

-

Relating to the use of one's will.

-

When people say Typhoid Mary they are referring to Mary Mallon, a cook who is believed to have infected between 52-122 peoples with typhoid fever. She was the first person in the US identified as an asymptomatic carrier to Typhoid yet infected most of the families she cooked for and the people she cooked with.

-

Beliefs or practices that are presented as scientific but lack a basis in the scientific method.

-

German philosopher known for his contribution to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism and for being a support of the Nazi Party.

www.nccu.edu/1079/heid_sch.pdf (Link from play)

-

A delayed vaccine schedule means spacing out shots more than the standard schedule (like CDC/AAP), often due to parental concerns about safety or feeling overwhelmed, but these alternative schedules lack scientific evidence and leave children vulnerable longer.

-

Core concept in finance and decision-making that describes the inherent trade-off between the potential for positive outcomes (reward) and the potential for negative outcomes (risk).

-

A collection of financial investments, including stocks, bonds, cash, and other assets, held by an investor to achieve specific financial goals.

-

"Big Pharma" refers to large, influential pharmaceutical companies, often viewed critically for prioritizing profits, high drug prices, and aggressive marketing, contrasting with public health goals, but also credited with developing life-saving medicines.

-

Pharmaceutical company

-

Historic movie theatre in Oakland California

-

A meditation labyrinth is a single, winding path used for walking meditation to quiet the mind and reduce stress. Unlike a maze, it has no dead ends, with the same path leading inward to the center and back out.

-

This phrase is referring to two different mass evacuations from World War 2:

Pied Piper, refers to Operation Pied Piper which was an evacuation operation by the British government to protect children and pregnant women from expected german air raids. It was intended to save lives but led to mass separations of families.

Death marches referred to the forced evacuations of concentration camp prisoners by Nazi Germany at the end of WW2 where hundreds of thousands people died.

-

Natural selection is the core mechanism of evolution where organisms better suited to their environment (with advantageous, heritable traits like camouflage or beak shape) are more likely to survive and reproduce.

-

A medically induced coma is a temporary, drug-induced state of deep unconsciousness, used by doctors to protect the brain from swelling or seizure activity.

-

Portion of plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes.

-

Not to be relied upon; suspect.

-

Happens when enough people in a population are protected from a contagious disease (via vaccination or prior infection) that it slows or stops the spread.

-

Normal, healthy debate over evidence, methods, or interpretations. It drives progress by challenging ideas but it can stem from different assumptions, incomplete data, or external factors, though it can often lead to a confused public.

-

A creationist is someone who believes that the universe and all life were created by a supernatural, divine being, typically God, rather than by natural processes like evolution.

-

An owner of shares in a company.

-

A person who settles a dispute or has ultimate authority in a matter.

-

A statement or belief that is true for all people, at all times, and in all situations, regardless of personal opinion or cultural context

-

Unconscious favoritism toward or prejudice against people of a particular ethnicity, gender, or social group that influences one's actions or perceptions.

-

The inherent human tendency to make mistakes.

-

Use weakened forms of virus to trigger immunity by mimicking natural infections.

-

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, unexplained death of a baby younger than one year old.

-

Town in California, across the Gold Gate Strait from San Francisco.

-

Time between exposure to an infectious agent or toxin and the first appearance of symptoms.

-

A systematic decision-making tool that weighs the total expected costs of a project or action against its total anticipated benefits

-

A specialized U.S. federal court handling claims for injuries or deaths from vaccines covered by the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (NVICP), offering a no-fault, streamlined legal process for individuals to receive compensation without suing vaccine manufacturers directly.